“What we don’t understand is grief is the death of something. A marriage, a job loss. This is a collective loss of the world we all lived in before the pandemic. And like every other loss, we didn’t know what we had until it was gone…Grief. It is grief.” –David Kessler, author of Finding Meaning: The Sixth Stage of Grief

During the 2020 presidential campaign, Joe Biden’s success was not only repudiation of the incumbent but also endorsement of his brand, something close to Empathy™. At the time – 250,000 dead and counting, no ready vaccines, no end in sight to layoffs or online school or social distancing – we needed a griever-in-chief, a leader who understood pain and could offer hope that things would, in fact, get better. By now we all now know the Joe Biden story. The loss of a young wife and baby daughter, the later loss of an adult son. No matter our opinions about his politics, his heartbreaking expertise in grief is undeniable.

In the past three years, grief has transformed our culture. The hashtags #griefjourney and #griefandloss have billions of views on TikTok. Death doulas—folks who support people and their families around dying—are all over Instagram. Anderson Cooper’s grief podcast, All There Is, reached #1 on the Apple Podcast charts within days of its September release. And we’re seeing our first pandemic novels, marked by grief: Elizabeth Strout’s Pulitzer-winning characters, now divorced, find themselves podded on the Maine coast in Lucy by the Sea. In Our Country House, Gary Shteyngart writes a group of friends isolated together in upstate New York. I hesitate to call this a trend – it is a global reckoning – and of course grief is not new, in literature or in life.

***

My partner C died in 2014 at age 41. His life was complicated and so was his death. The loss rearranged something fundamental in me. Friends and family assumed I would write about it, and so did I. I made a few floppy attempts but could never put my words in the right order. It all sounded false, pretentious. My drafts resembled TV after-school specials, with a moralistic quality I didn’t actually feel. I couldn’t find a path into telling my story. C and death and our relationship loomed too large. It was too hard. I felt totally broken anyway. I gave up for a while, and instead I read other writers who had put grief on the page.

Yiyun Li’s singular novel Where Reasons End is a book-length imagined conversation between a grieving mother and her dead son, Nikolai. Li’s 16-year-old child had died by suicide in real life, shortly before she began writing the book. The novel is set in a netherworld, a place outside of time where only mother and son exist. The dialogue moves among intimate arguments, inside jokes, and the unanswerable questions that all of us left behind must grapple with eventually.

“How can anyone believe that one day he was here and the next day he was gone?

Yet how can one, I thought. How can one know a fact without accepting it? How can one accept a person’s choice without questioning it? How can one question without reaching a dead end? How much reaching does one have to do before one finds another end beyond the dead end? And if there is another end beyond the dead end, it cannot be called dead, can it?

How good you are, Nikolai said, at befuddling yourself.

Fuddled, muddled befuddled, I said. Every time you say something I have to turn to the dictionary. Every word has ten more definitions I have missed.

Nobody says you have to know all the definitions.

What if one could only make sense with those missing definitions.

Most people won’t bother themselves with that, you know.

Most – I said, and then, to be less generalizing, I revised myself – many people don’t have to go to this extreme as I do not to lose someone. I thought about what people said, that there are ways to keep the dead alive, that it’s our love and memory that carry them with us. But was that enough for Nikolai? Any lesser way would only make him vanish again. He had outwitted many people. There was no reason he would not do it again.

If Li’s writing carries a nearly unbearable intimacy, Tom Perrotta’s 2011 novel The Leftovers, since made into an HBO series, is grief sensationalized: a dystopian America where those left behind post-rapture are largely resigned to the new world order. But a cult, the Guilty Remnant, cannot abide the collective will to move on; they make it their business to remind the public of all that has been lost forever. A “Hero’s Day” parade celebrating the Departed starts off hopeful, with speeches, high school bands, a new monument to the dead. Then dozens of Guilty Remnant members interrupt the feel-good event. They hold up letters spelling out “DON’T WASTE YOUR BREATH.”

In the novel, the cult fades away into the woods. But in the TV version, the townsfolk get angry. Really angry. They want this stupid cult to just leave them alone and let them have a normal, civic-minded memorial day. No one wants to be reminded of their inner horror. A fistfight ensues, and the day that’s supposed to help people return to normal turns into a bloody brawl. What I see here: a manifestation of grief.

Who can forget the battles over masking, rooted in fear – fear of an unknown virus but also of losing a way of life, made more desperate by the creeping sense it was already gone. So much of our politics is driven by this same fear. We tend to elect leaders who can assuage it, either by promising decisive (and sometimes wrong-headed) action or, in the case of the current president, projecting calm in a storm.

I am reminded of James Baldwin’s 1953 essay “Stranger in the Village.” It is an account of being the only black person in a Swiss village, but it also sought to characterize American racial politics. “People who shut their eyes to reality simply invite their own destruction, and anyone who insists on remaining in a state of innocence long after that innocence is dead turns himself into a monster.”

***

When C died, what I would have given for a conversation with the dead like Li described. I often went through my days thinking everything was fine, but then I’d have these flashes of want. Of that specific fantasy. A chance to sit next to him, hold his giant, calloused hands and just talk, and also not talk at all. And if that was possible, I dreamed I might also be able to travel back in time and keep him from dying altogether. Or at least learn how to locate him in the universe now that his body was gone but his spirit still felt so close sometimes. In those moments, any kind of normal felt very far away.

As Biden once put it: “Just when you think you’re going to make it, you’re driving down the road and you pass a field and you see a flower, and it reminds you. Or you hear a tune on the radio. Or you just look up into the night and, you know, you think, ‘Maybe I’m not going to make it, man.’ Because you feel at that moment the way you felt the day you got the news.”

***

Poet Maggie Smith on the May 23, 2022 episode of the Depresh Mode podcast:

“A friend of mine said after my divorce ‘Well, at least this experience wasn't wasted on someone who's not a writer ‘

I was like, ‘Wow, um, I would prefer you know, another way.’”

I don't want this lemonade. I didn't want the lemons and I don't want this lemonade. I've had to make it. If someone hands me material and it happens to be really painful, as a writer, that's just what I do.”

But I'm really uncomfortable with the idea of harm as material, like we're supposed to somehow metabolize and bake something good into it. Sometimes maybe that's the best. That's the best we can do is the lemonade but, but wouldn't it be nice to just not be handed the lemons and get to write about something else?

My life would be better for not having that material.

***

At this stage, more than 6.7 million people worldwide have died as a result of Covid. Of those, 1.1 million died here in America - an unfathomably large number, nearly the entire population of Dallas. And one in 13 adults in the United States have symptoms of long Covid, health problems that have persisted for three months or more that they did not have before they contracted the virus.

If this wasn’t already too much to bear, consider that suicide rates were up 4 percent in 2021 over 2020, overdoses are multiplying exponentially, and the crisis in mental health care demand continues to strain capacity.

We are, in a word, unwell.

***

The jockeying around 2024 presidential candidacies has already begun and might soon explode into public view. It’s hard to know how much we will welcome the griever-in-chief moving forward. Biden himself has declared the pandemic over and has begun to initiate corresponding policy changes, including eyeing an end to the public health emergency designation for Covid. But he seems to be following the will of the people. Many of us are eager to move quickly through our grief and embrace the change, especially those who have escaped the worst consequences of this deadly disease. There are Guilty Remnants among us, but collectively we are moving on. And as we do, Empathy™ may no longer feel required. Maybe we’re in what David Kessler calls the sixth stage of grief, past acceptance and onto finding meaning in what we’ve lost. In that stage, other brands of leadership start to appeal – a fresh-faced do-over; a get-it-done back-to-business job creator.

But as Joe Biden might tell you, there is no time limit for grief. Not three months after a death, not three years. As he said in a 2012 address to the families of fallen soldiers: “There will come a day, I promise you… when the thought of your son or daughter or your husband or wife brings a smile to your lips before it brings a tear to your eye. It will happen. My prayer for you is that day will come sooner rather than later. But the only thing I have more experience than you in is this: I’m telling you it will come.”

We can only gradually adjust our relationship to grief. We learn to refocus our life’s lens to the holes where there used to be humans. Eventually we can accept that bad things happen, and people just die, too soon, too late, from cancer or Covid or no reason at all. But the ache remains, whether we acknowledge it or not.

***

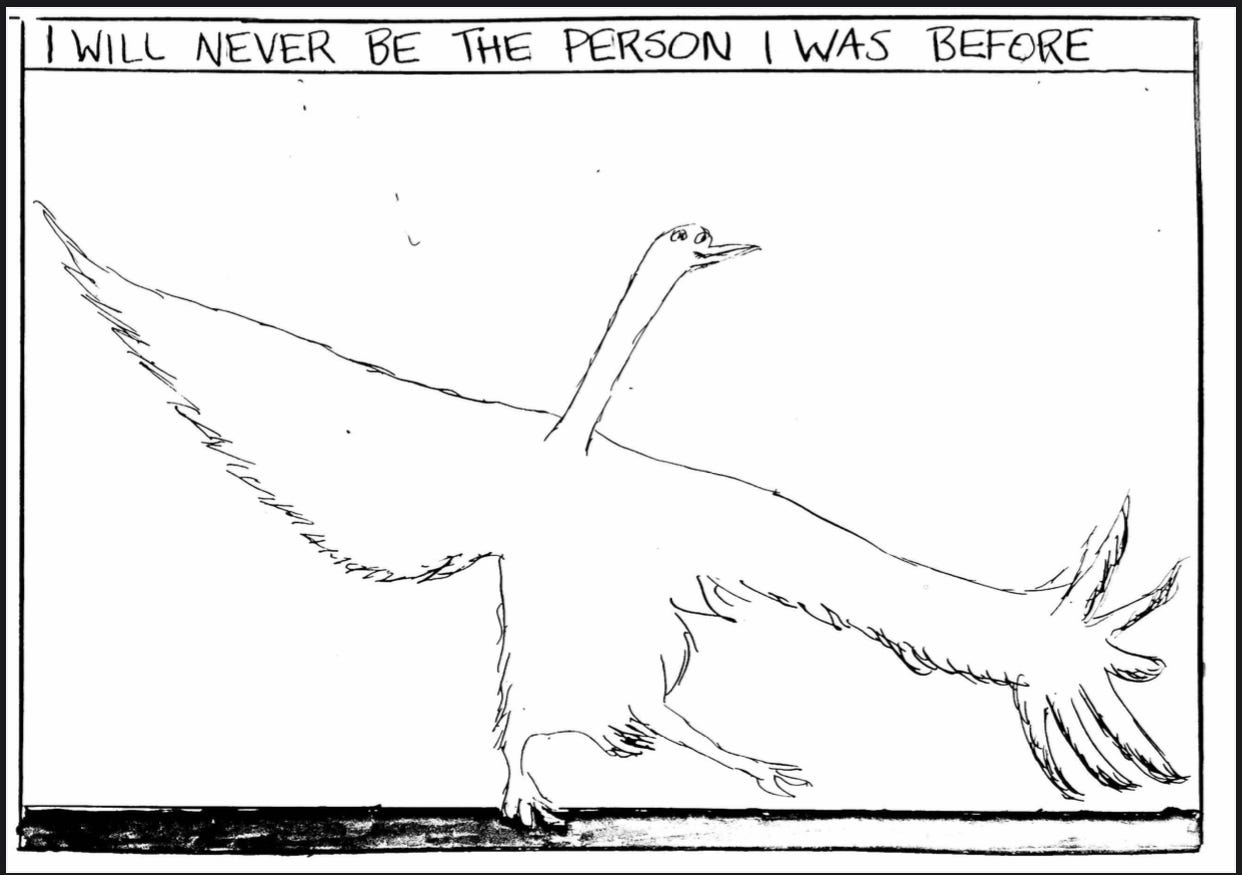

I did eventually write about C. I first found my way in by drawing comics about animals living out the worst parts of grief, the things too hard for me to say aloud. In January 2020, on a solo trip to Mexico, I watched pelicans dive bomb for fish in Holbox and something about that moment made the narrative fall into place. I spent the pandemic writing a memoir manuscript. It’s a container for the difficult parts of him and me and our relationship and grief. All this work took years of my life, and it’s unclear if it will ever be published. Did the writing help? I still want to throw a chair out a window sometimes. But the grief has dulled.

From Where Reasons End:

“Days are not the only place where we live, Nikolai said.

Time is not the only place where we live, I said. Days are.

I don’t have days to live now.

And yet I have to live in days, I said.

I’m sorry, he said.

Days: the easiest possession, requiring only automatic participation. The days he had refused would come, one at a time. Neither my allies nor my enemies, they would wait, every daybreak, with their boundless patience and indifference, seeing if they could turn me into a friend or an enemy to myself.

Never apologize, I said, for what you have let go.

Thank goodness for your intimacy and poignant reflection. Perhaps your talent and gift comes from your honesty to bravery share from your heart 💜 and mind.

What a poignant and piercing essay. I love how you pulled so many pieces into a mosaic, and introduced me to as-yet unfamiliar authors—and podcasts! I found myself recalling Lincoln at the Bardo and wondering where that imagining of grief and politics would weave in here.