WE BOUGHT THIS house last summer, a new baby in our arms and our elderly dog padding alongside us. More space, we thought. Space is the thing we need. In the winter I put my too-small desk in the window of the guest room and worked on my novel. One day in February a woodpecker began pecking at a half-dead tree limb stretching over the back deck. Its wings were striped black and white, and I wondered if it was hollowing out a hole to fit a nest. It visited every day and I liked seeing it. It was as if I knew this bird – as if we knew one another.

The woodpecker tapped on the tree and I tapped on my keyboard and sometimes I could forget the world was, slowly, thawing. Our friends without young children went to dinners, movies, concerts. They got on planes and went to weddings and Europe. Gone were the days of Friday night zoom calls, of feeling like we were all in this pandemic together. But I understood. They were vaccinated; they were moving on. Meanwhile, we sat in our house and waited. The baby vaccine is coming, the health experts said. Over and over they said it. Two months from now. Now just two months more.

Then it arrived. And when our baby had her final shot, just this past July, we thought: Now what? We still didn’t want to get sick; she was still too young to mask. And truthfully, some parts of pandemic life suited us as new parents. Cooking in, less travel, fewer nights out – it all saved us hassle and logistics and money.

Parenting, we have learned, is nicer when there is no need to be anywhere on time.

***

These two-and-a-half strange static years have reminded me of the time when my own physical world was small. Not from fear of giving an unpredictable virus to my child, but because I was a child. Ours was not a family that traveled. My mother first boarded a plane to take me to college; my father had been a paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne, but after he left the Army I never knew him to fly again. If I wanted to leave Wichita or to experience something new, and I usually did, it had to be through a book.

Just after my daughter was born, I turned 40 and read Jhumpa Lahiri’s novel Whereabouts. The unnamed protagonist, a woman in her 40s, has lived a pleasant but restrained life in Italy. We dip into her days and they are ordinary. She is alone. Part of her needs the solitude, relishes it, and part of her wonders what more her life could hold. She insulates herself from friends, colleagues, lovers current and potential, her mother.

The chapters are brief and titled by the woman’s whereabouts. On the Street, At My House, In the Mirror. I imagine capturing my own life in this way. In Bed, yes. At My Desk, yes. In My Head, yes, definitely. As I name and capitalize these places, they begin to feel significant, less mundane, even worthy of my desire to cocoon myself inside them.

This book’s places are somewhat lovelier than mine, or at least are vestiges of my pre-pandemic life. The Beach, the Museum, the Ticket Counter. But despite our differences, this woman – I feel like we’re friends. Like the woodpecker. I think it’s because it feels like she is speaking to the reader and the reader alone. She had a therapist but not any longer. She tells us, but not her friends, her true reactions to their conversations. We hear about dinners and encounters in a perfunctory, after-the-fact way. We come to understand she’s attempting to articulate memories she’s still trying to process, the way we all might record things in our diaries.

In The Art of Intimacy, Stacey D’Erasmo writes:

“I have noticed that the intimacy we feel as readers is often generated far less by characters turning to one another and saying intimate things or doing intimate things than it is by a textual atmosphere, or maybe one should say a biosphere, a gallery, a zone that both emanates from the characters and acts upon them very deeply and personally… The odd and powerful space between, the space where we meet, isn’t only the medium for intimacy: it is, sometimes, the thing itself.

It is terribly intimate to read someone’s private thoughts, those they save for themselves.

***

This week I am in Covid quarantine. Today is Day 5. I can hear my husband and daughter, now 20 months old, playing downstairs, laughing, reading books in the potty. We FaceTime over meals. She understands Mami is sick, Mami is sleeping.

I am not particularly sick. I got my bivalent booster two weeks before I was exposed. Even though I tried very hard for a long time to not get it, having Covid is not what’s bothering me. Having Covid is temporary, I hope. As I sit here by myself, regretful that my husband must solo parent, guilty for taking pleasure in my isolation, the thing that feels most difficult to resolve is not my congestion but my complicated feelings about loneliness.

This strain of loneliness seems to me an amalgam of the pandemic and new parenthood and moving across town and trying to write a book. It’s the physical and emotional distance I feel from friends. A lingering idea that masking and testing make sense and need not be completely abandoned. A career that demands seclusion when I crave connection. I have been so lucky, all this time, to have a life filled with friends and family and work I want to do. And yet I feel a retrenchment in myself, an unwillingness to give up my hunker-down mentality. In non-pandemic times maybe this would have been seen as nesting, focusing on my little family. What is late-blooming reckoning with post-pandemic life and what is the beginning of middle age? Whatever it is, what do I do with it?

Stacey D’Erasmo, again: “When I come to fiction, both as a reader and as a writer, I wish for it to make visible something that, without it, I would perhaps have never seen. The reason that I might not have seen it isn’t that it is so rare, but that it can sometimes be nearly impossible to see what which is as omnipresent as air.”

It is late. My daughter is sleeping; my husband is tired. I hear his steps, slow up the stairs. He stops outside our closed bedroom door. Crouches to slip Halloween candy through the slim crack at the floor.

***

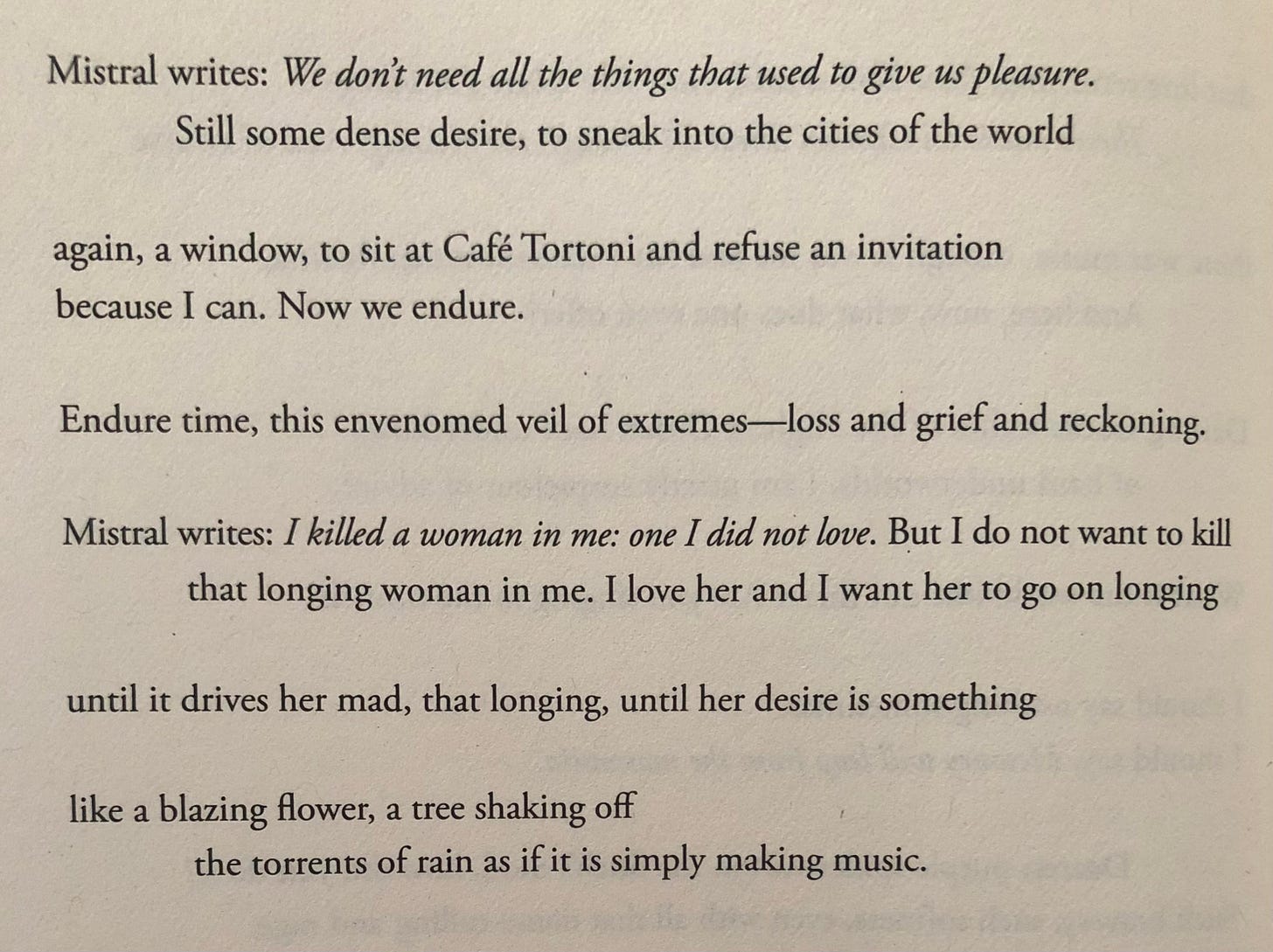

An excerpt from “Banished Wonders,” a poem in The Hurting Kind by America’s newest poet laureate, Ada Limón.

***

Last winter I watched that woodpecker for weeks. It pecked and pecked some more. It came and went and came back again. Its little body almost disappeared inside the hole it made in the branch. I imagined a nest would appear come spring and the idea of a bird family in our tree made me happy. But then I went to the kitchen and saw something on the deck. The branch had cracked precisely where the woodpecker had been pecking and crashed down onto the deck railing. If a nest was its intent, the bird wasted weeks of work. And now we were missing a branch, albeit one that probably needed to come down anyway. So perhaps the woodpecker had done us a favor.

People turn all sorts of places for communion. Relationships, religion, jobs, fandom. Mommy groups and yoga class. Pussy hats and QAnon. Whoever happens to live next door.

I say “people,” but I mean me too, writing this newsletter in an effort to connect. Out of a hope that having a dialogue with you about books and the world will be an outlet for my natural extroversion, a source of energy to complete my own novel. I am wary of conclusions, of tidying things up too much, but perhaps subconsciously I’m telling myself to go to my room until it’s finished. Or perhaps that too is an excuse.

I saw the woodpecker once more after the breakage. Maybe I was projecting, but it looked confused. It tapped around the broken limb, and then, dissatisfied, it flew up onto a smaller, less hospitable branch. And then it flew away and left me.

I miss its tiny beak, its singlemindedness.